Published June 21, 2018

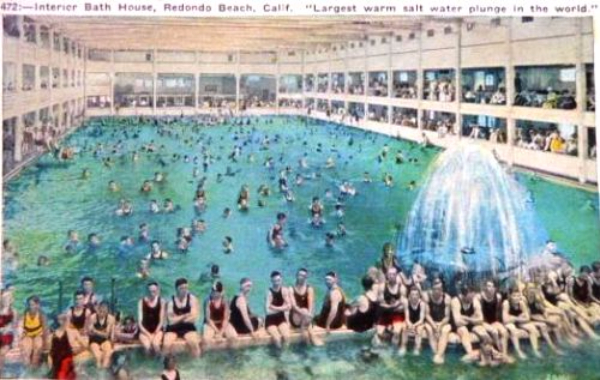

Saltwater Bathing Houses

For those of y’all that aren't in Charleston at the moment, here’s the latest weather update: it’s hot as Hades and has been for a while-- even though it’s only June. To anyone out at the beach right now: GOOD IDEA. But back before getting to the beach was (relatively) easy, people living downtown found other ways to beat the heat. Taking the waters in Charleston meant going to a saltwater bathing house. Perhaps we wouldn't be all hot and bothered if we still had a couple of these. What do you think?

The Bathing Houses of Charleston

Throughout the 1800s, Charlestonians used saltwater bathing houses for swimming and recreation. They were set out beyond the low-water mark in the harbor and were connected to higher ground by a bridge. Some were floating and some were built on brick piers, and they generally had separate facilities for men and women. Although the private bathhouses attracted paying patrons, they were not profitable for owners. They frequently closed when damaged by storms and the upkeep and repairs were extremely costly. The City had plans to take over one and build two more at the turn of the century, but alas, it did not happen.

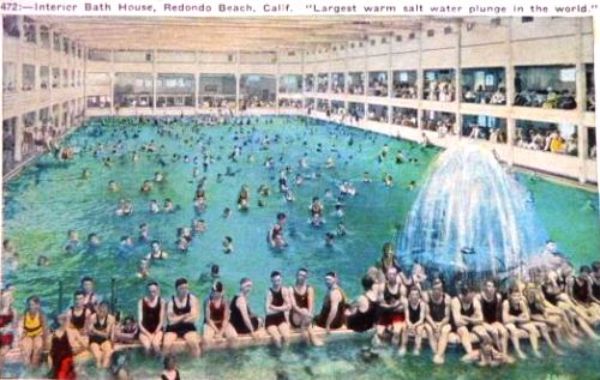

Interior of Battery Floating Bath, NYC, circa 1898, by E. Stopff. Columbia University Library/Information Services.

Early on the Cooper

One of the first bath houses downtown floated 100 yards from the shore and was connected by a bridge to East Bay Street near the end of Atlantic Street, according to a City Gazette advertisement on June 9, 1814. It was originally planned to be “a circular floating bathing house 250" in circumference...with forty capacious private bathing rooms lighted by Venetian windows, a large swimming bath in the center." While not as accommodating as originally planned, the bathing house was popular. On July 1, 1815, the City Gazette stated that “repairs to the Salt Water Floating Bath are complete, and the house hauled out to its moorings. It is put afloat, we understand, by means which secure it against the possibility of sinking; and the bathing apartments are so lined as effectually to exclude those marine animals which were so troublesome last year." Hmmmm...crabs, jellyfish, sharks, maybe? Okay, if someone decides to build another floating saltwater bath, please be sure to get this part right the first time!

Interior of Swimming Bath, Harper’s Weekly, August 20, 1870. New York Historical Society.

According to a March 31, 1970 article in the News & Courier, there was another bathing house off of Lauren’s Street in the Cooper River, an octagonal building covered by a roof with windows opening to the lower level and an open section with railing above. An undated advertisement states that it evidently had “sustained no material injury from the late Equinoxial Gales" and was equipped with “two shower baths for the accommodation of those who prefer them." Notes accompanying the Halsey Map at the Preservation Society of Charleston indicate that this was the Frazer Bath House, which operated from 1820-1835 at which time it was “almost entirely destroyed" by a hurricane and beyond repair.

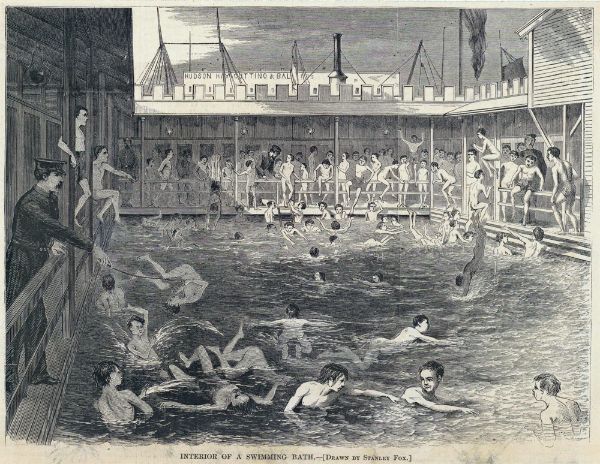

C. Drie. Bird's Eye View of the City of Charleston, South Carolina. 1872. American Memory, Library of Congress

White Point Garden

But probably the most elaborate and successful bath house was the large structure off of White Point Gardens. Several maps show it in line with Meeting Street, although some place it closer to the foot of Church Street. Built in 1842, the facility was endorsed by the community as the importance of sea bathing for health and recreation was recognized. Children were encouraged to take lessons in swimming, and the owner of the private enterprise agreed to open the bath house free of charge to the children of the orphanage on one day every two weeks. There was a promenade encircling the swimming pen and musicians frequently came over from the band concerts in the park to play in this upper story as fireworks were displayed. During the Civil War, the tall structure was used as a lookout tower.

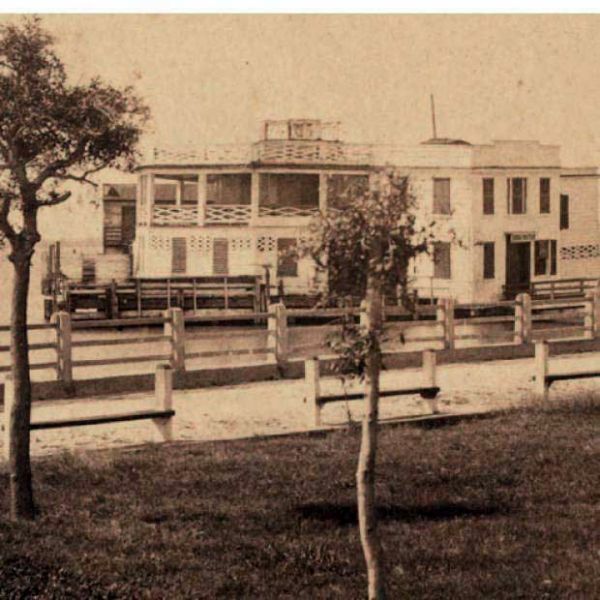

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. "Bathing house and Battery, Charleston, S.C." The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

The McManmon family owned the bath house off the battery when the hurricane of September 28, 1874 struck Charleston, and they barely survived. Hundreds of people were lined up along the battery as “Mrs. McManmon and her two little children stood at the open window with arms outstretched." After several boats were unable to reach them, a man tied a rope around his waist and battled his way through the surf to reach them. After he saved McManmon’s daughter, the eye of the storm came and two small boats were able to retrieve the rest of the family. The next day, only “a rickety crumbling ruin and the stumps of the posts upon which it was built" were left. By 1877 another had been built near the site, but these structures were awfully close to the city’s main tidal drain at the foot of Meeting Street. According to notes left by William Gaillard Mazyck, swimming was not allowed when the tide was going out to avoid contact with the refuse. After this bath house was destroyed in 1880, another “Salt-water Bathing Pavilion" was built at the foot of King Street. Torn adrift and wrecked in the cyclone of August, 1885, it was rebuilt as a smaller structure which was in turn destroyed by the storm of August 27, 1893. Well, it’s a good thing we have much better building materials these days, right (hint-hint)?

Sunset from the Battery, Charleston, SC (circa 1900-1910), Detroit Publishing Company Photograph Collection, LOC

Ending at West End

Charleston’s last saltwater bath house was the West End Bath House, built in the mid-1890s at the foot of Tradd Street after a portion of the marsh had been reclaimed near the Chisolm’s Rice and Saw Mill (which is where the Coast Guard Base is now). Murray Boulevard had not yet been built. Mr. C.W. Bailey built and attended the structure for at least five years, making extensive and expensive repairs between summers--including replenishing the gravel that lined the bottom, making a clean, smooth bed. An 1886 advertisement in the Post stated that a single swim cost 25 cents ($5 per season), plus 5 cents each for bathing suit and towel rental. The next year, prices were lowered to attract more customers, and bathing suits were issued free (you still had to rent a towel). Although some Charlestonians held to the custom of spending time afloat the pavilion swimming, relaxing, and taking in the fresh sea breeze, the business could not be maintained. In 1903, the City was supposed to take over the baths--and build two more--but a 1906 photograph shows the structure deserted and dilapidated. Today, if you’re interested in swimming in the harbor, consider swimming in the Low Country Splash with Ellery or perhaps the 12-mile Swim Around Charleston. Sadly, our saltwater bathing days are over in Charleston--until someone (please!) builds us a new one.